Bugs + Movies =

Right-click or Command+click to download

Music in this show:

1. DMK, “Enjoy the silence”

2. Little Cow, “What will be”

3. Henry Mancini, “Baby elephant walk”

4. Thomas Newman, title track from Brothers

5. Yma Sumac, “Tree of life”

6. Spanglish Fly, “Let my people bugalú” (Clay Holley and Jeff Dynamite remix)

— — — — —

Jake Oelman is quick to point out that, yes, his dad lives in Colombia, South America; but no, his dad is not a drug dealer.

Jake’s father, Robert Oelman, was a psychologist working in Boston until he left his career, moved to South America, and began photographing insects. Jake is a filmmaker based in Los Angeles. Right now, father and son are collaborating on a documentary film. Jake describes it as an exploration of “how a person goes and changes their life path from being in one profession to taking up something completely different, in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language.” The film highlights Robert’s photography and his fascination with the insects that model for him.

To date, Robert has survived his interactions with diverse, mysterious bugs in the jungles of South America. But Jake shared a story about a close call for his dad. “He was watching a television program back at his house in Colombia. A program about this deadly spider–one of the most deadly spiders in the world. He was like, ‘Wow, that thing looks really familiar; I’ve seen that before.’ So he went back and he actually had this photograph of the spider.” Robert figured at the time that the spider was potentially dangerous. Jake said, “If somebody doesn’t want you to take their photograph, they’ll let you know that they don’t want their photograph taken. And the same is true with the insects.”

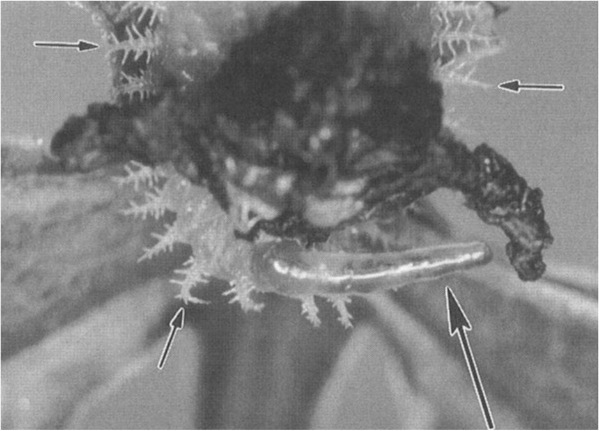

How Robert Oelman survived a photo shoot with this creature is anyone’s guess.

Robert actually built a house in Colombia and began by photographing hummingbirds in flight. He keeps dozens of hummingbird feeders at his house, “and they come in droves. It’s a pretty magical experience when you’re there for the first time, because you’re in the house, and you just hear this sound…” Jake describes it as “just energy swarming around you constantly.” Taking pictures of the hummingbirds seems to have strengthened Robert’s “photographic eye”, and he eventually transitioned to insect macro photography.

“He saw an insect one day, he photographed it, and then when he looked at the photograph, he was like, ‘Whoa! I can see more in the photograph than I can with my naked eye!’ And the lightbulb went off, and he’s been photographing them ever since. He just feels as if he could never stop finding new things to photograph in the insect world.”

“Since his eyes are open to it, then my eyes become open to it.” Jake’s sentiment permeates the film and is underscored by the film’s title: Learning To See.

It was Jake’s idea to make the movie. His dad was reluctant, initially, to be the focus of a documentary. But Jake was persuasive. He told Robert, “You want your work to be seen. You’re photographing things that some people have never been able to photograph before. You’re photographing things that may or may not exist 5 or 10 years from now. You’re photographing things that little kids have never seen.”

Robert’s process involves capturing insects and bringing them to a makeshift tent studio in the Amazonian rainforest. “They’re jumping all over the place. The first time you have a really big katydid crawling on your arm…I have a respect for it,” says Jake. “Because all of a sudden, now I’m in his world, so I can’t be squeamish. I have to have a respect. … There’s something surreal happening in those types of experiences.”

Jake wasn’t always comfortable with bugs, and he and his dad weren’t always close. “My parents divorced when I was really young. I think once my dad became a photographer, we became closer. I had already been working in film for quite a while before that, so when he started to take photographs, … I think that we started to relate to one another’s professional aspirations. So that kind of brought us in a little bit closer, which is funny to think that he moved so far away, and then we got closer as a result of that.”

But just like Robert occasionally finds a spider of death hitchhiking in a pile of collected leaves, Jake laughs when he says that “… we can still bump heads, too, which will be interesting. When it’s two artists coming together in a remote part of the world … Who knows; that could even make the story, as well.”

Jake and Robert are filming one more trip outside of Colombia to finish the project. “Now, the place that we go to in Peru–it’s a pretty long trip to get there. So, my understanding is that you fly into Cuzco. And then from Cuzco, you take a bus … down into the jungle, and then you get on a canoe. It takes two days to get from Cuzco to where we’re going … an outpost in the Manu territory of Peru. And we’ll just be going on expedition every day.”

So Jake and Robert have a few more bugs to hug for their film, Learning To See. And with their Kickstarter campaign, they have a chance of actually completing the project. With the kickstarter, they’re asking for some support to fund the last leg of their project. If you want the documentary to exist (and maybe get a digital download, DVD, or even photographic art as part of the deal), you are expressly invited to do that thang. They’re passing the hat for just 7 more days.

Update: Success!! Jake and Robert’s kickstarter has been funded! Good work, everyone. Looking forward to seeing the film.

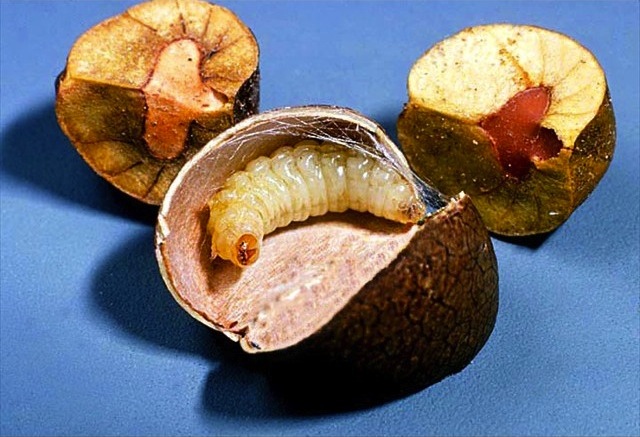

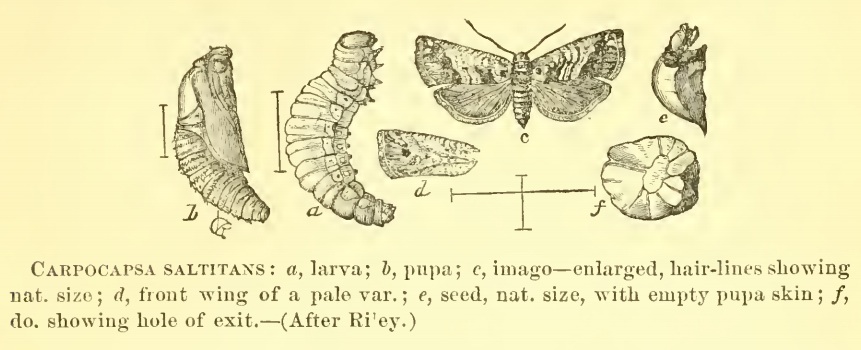

Robert Oelman does not restrict himself to photographing insects.(Click on those thumbnails to view larger photos)